Firmware Updates

27 Mar 2022You may or may not know just how much I hate printers. They are the worst consumer product experience you could ever dream of. Drivers and DRM and ink that costs more than champagne – it's the type of subject matter that's easier to rant about than shooting fish in a barrel.

I solved my printer problems long ago, by moving away from the consumer tier and getting an industrial thermal printer we lovingly call a Zebra. It's a 6-by-4 label printer, so it doesn't really fill the same shoes as a run-of-the-mill inkjet, but in principle it fixes all of the terrible attributes in one swoop. There's no ink to replace, and it's built to a quality that will last. It's designed to spit out labels all day, every day, for decades at a time. Nothing to go wrong, nothing to replace except the labels we're printing on.

The death of my Zebra printer hit hard.

Aside from the misery induced by having to finish the day's parcels the old-fashioned way – writing out addresses by hand, queuing up in a post office behind the other filthy patrons, enduring their cringeworthy interactions with the incompetent staff and paying a premium for the privilege – the real pain is that of betrayal. Zebra printers are workhorses, they last for decades. They are not supposed to break.

So we're faced with a decision: to repair, or to replace. Consumer products get replaced. The Zebra deserves a repair. But the further we delved into the process, the further our printer, and the company that produced it, fell from that platform we'd elevated them to.

The symptom

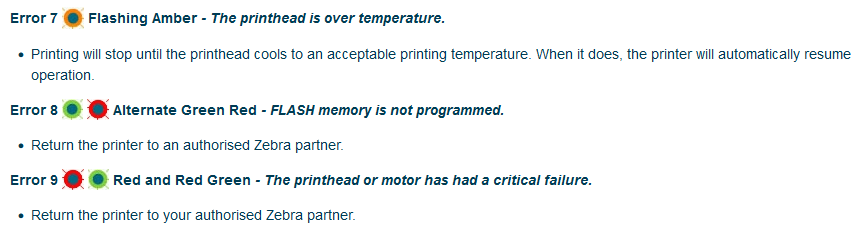

Apart from the fact that it doesn't print, the only symptom we've got is that the status light is flashing red and green.The official manual, and the internet at large, have conflicting interpretations of this status pattern. The only thing that can be agreed on is that it "needs service". Green and red could be a flash memory error, but red and green would be a printhead or motor failure!

I realize it's difficult to convey much meaning with a single status LED, but this level of ambiguity, where I can't even determine if the failure is mechanical or electrical, this is cutting out a new niche of poor user interface.

Based on the situation where the failure occurred (on power-up, not during a print) and also based on some prior knowledge of printers and CNC controllers of this era, I'm reasonably confident the problem is with the flash memory.

A little exposition

You're a manufacturer. You sell some hardware. That hardware has electronics in it, which these days means a microcontroller running some software. "Firmware" if you're feeling fancy.That software needs to live somewhere. Back in the day, it'd be a UV-erasable EPROM chip, these days it's on flash memory.

One of those niggling little problems, the type that gets forgotten about until the very end of the development, is that after you've sold your hardware, it may be that you need to change that firmware. But it's only occasionally this needs to be done, right? So you hastily chuck together a firmware-update mode and duct tape it onto the product.

With the advent of IoT, and the myriad security flaws unleashed upon the consumer world, firmware updates have become routine and commonplace. About the only good thing to come out of the era of the WiFi coffee machine is that, by necessity, the firmware update process has been streamlined. It's still painful, but it's not on the same level as an un-networked printer firmware update. I have experienced far too many of them in my life.

Expect:

- a windows only

.exefile which installs custom drivers and a special program for firmware updates - a command line interface if you're lucky, or a broken/unintelligible GUI otherwise

- complete inconsistency of terminology, where "download" can mean either direction

- obfuscation or "encryption" of the firmware images

- being forced to register with the manufacturer to get hold of any of it

This isn't limited to printers, even today products are being released with the same mindset. I recently performed a firmware update on a newish MIDI keyboard, partly just to see if the process was any less abhorrent. After installing their software, which is also used to configure the keyboard, and downloading their obfuscated firmware image, the update took place over SysEx over USB. Par for the course. This culture is so pervasive that even the synthesizer I designed for Aaron was eventually released with a proprietary program that manages its firmware updates. It's what people expect.

Corruption

Flash memory doesn't last forever. It has a limited number of write cycles, often as little as 10,000. SD cards and USB memory sticks get around this by spreading the writes, wear-levelling so if you overwrite a file, it's actually getting written to somewhere else, rather than hammering the same physical part of memory.I don't know if this information was secret ten years ago, but a lot of products seem to have completely ignored the concept. Many printers and CNC controllers, in addition to keeping their firmware there, write a copy of everything they print onto flash memory too. I don't know if there's a supposed advantage to this or if flash memory was simply cheaper than keeping the files in RAM. Either way, the more you print, the more you're spending your write cycles and heading for impending doom.

Even devices that don't smash their memory like this can suffer from the same problems, usually consumer-grade hardware with planned obsolescence anyway, but in some cases merely performing a firmware update is enough to recover the device. A full erase/rewrite may fix partial corruption, or maybe the system is clever enough, with some coaxing, to ignore bad pages.

So with great hardship I embarked on the process to update the firmware on my Zebra printer, but alas, it was not enough to bring it back to life.

Pain, or: how not to implement firmware updates

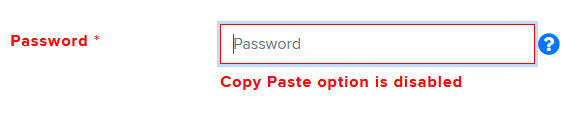

We've set the scene for the kind of experience we signed up for, but even I, with my jaded firmware update experiences, felt a new level of vexation.To download the firmware image, we have to register. To register, we have to provide a huge amount of personal data, including our postal address and phone number. Like any sane individual, I use a password manager and random generated passwords. Arbitrary password restrictions are one thing ("you must include at least x special characters" etc) but you know you're in for a fun ride when the designers of the web form specifically went out of their way to break compatibility with password managers.

They force you to type this out in full twice to register, and then again to sign in, so of course I went with something substantially less secure than I would otherwise have used.

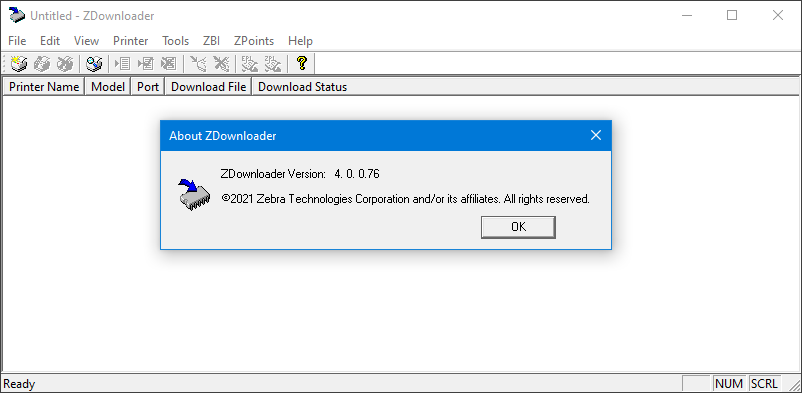

Zebra's firmware update utility is called ZDownloader, but after installing it, it can only be found in the Start Menu as the completely non-descriptive "FirmwareDownloader". How unlikely it could be, that someone keeps around a windows machine for precisely this purpose, and has half a dozen other firmware flashing utilities installed!

![]()

Click on it, and it's ZDownloader, but in the start menu Zebra or Z returns nothing.

The program itself has all the quirks we've come to expect as standard, with unexplained acronyms and terminology, but by far the most irritating aspect is the lack of a verification step. It's common practice to refuse reading out the flash memory, to prevent stealing the firmware image I suppose (even though we already have the firmware file). But after writing the image, and sitting through the progress bar, there's no confirmation of whether the process worked. All that happens is the selected "kit" (firmware) in the table returns to blank. If we could verify the memory, that would at least tell us if we're chasing the right problem here. (It still might be a critical motor or print head failure!)

Surgery

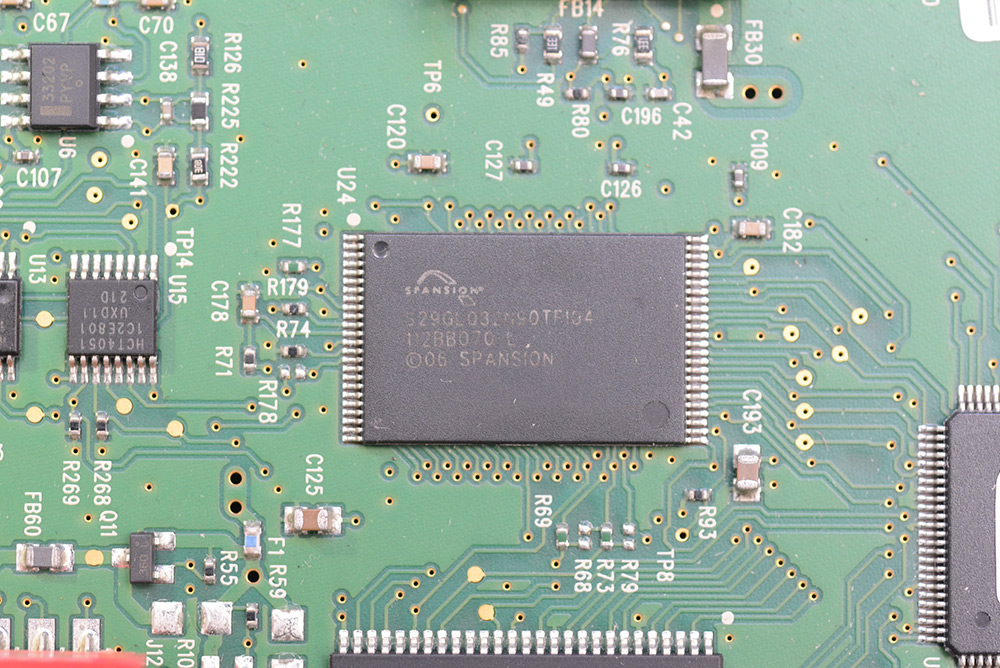

After dismantling the printer, the memory chip was easy to spot as it was hidden under a sticker with firmware version.

Although Spansion, the company that produced this chip, has long gone out of business, happily I found someone selling new old-stock replacements pre-flashed with the Zebra bootloader code. I suppose that says a lot. Enough people have faced this same problem that someone has made a business out of it.

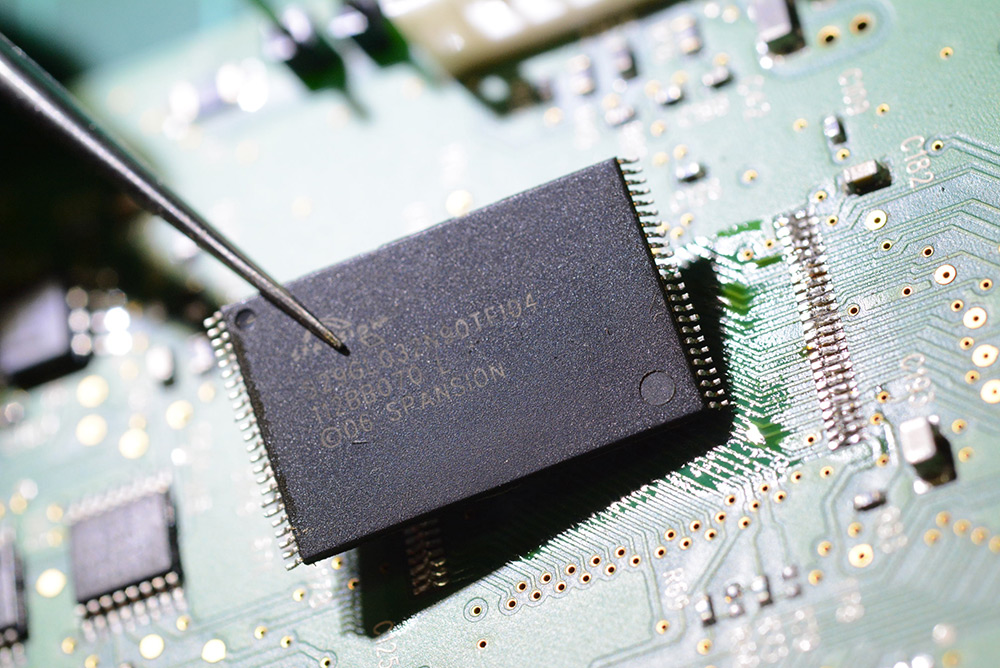

A touch of the hot-air gun got us started.

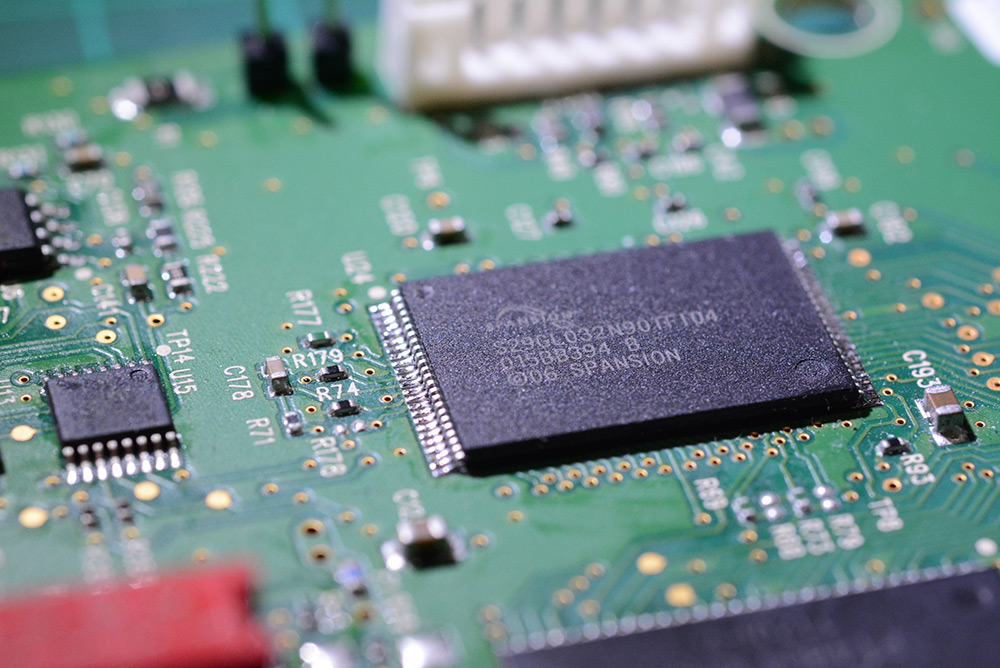

The pads were cleaned up and the new chip soldered into place. 'Course we lost our RoHS compliance in the process.

Reassembly, and then we've got to do the firmware-update process yet again, to christen the new memory chip. With that, the printer came back to life.

Proprietary protocol, proprietary driver, proprietary software and a terrible UI. These are the decisions that lead to a world where replacing a 48 pin, 0.5mm pitch surface mount memory chip is the easiest part of the repair process.

How to do it right

I wouldn't be as bold in calling out this utterly atrocious state of affairs if there wasn't a simple, obvious, right way to do it.At the time of writing, I've not yet released my Precision Clock Mk. IV. The design was finalized in 2020 but due to the chip shortage, I've not been able to mass produce it. That won't stop me boasting about its firmware update process though. I plan to release the design as open source, but these techniques are just as applicable to any hardware product.

The clock has a QSPI flash memory chip (SOIC-8, so much easier to solder than the Spansion chip above) which contains the timezone database, world maps and firmware images. An additional complication is that there are multiple processors on board running separate firmware images. I handle that smoothly with a chain-loading bootloader, but my approach would have been the same even for a single processor solution.

Here's how it works: You plug in the USB cable and it appears as a mass storage device. Any operating system, Windows, Linux, Mac, even a phone will be able to see the device without needing a driver. You copy and paste the firmware image onto the drive. Done.

In my case, the mass storage device maps directly to the QSPI flash memory chip, but it doesn't have to, the whole thing could be virtual. It's only on the next power-up that the image is verified and copied from the QSPI device to the internal memory, by a custom bootloader. The process is robust enough that even if you cut the power part-way through, it will gracefully recover.

Sure, it took a little more effort to design than the laziest possible bootloader. Sure, I could have rolled with the system bootloader or even asked my users to invest in a J-Link programmer. But I'm just an individual doing this in my spare time. An individual who wanted to do it right.

The solution is obvious, and any companies that release products in this day and age that inflict on their users the monstrosity that is the firmware update .exe should be ashamed.